Dr. Tran Chí Trung

Center for PIM-Vietnam Academy for Water Resources

I. Over view of Irrigation Management in would

1.1 Institutions for Water Resources Management

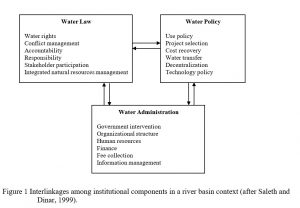

Institutions for water resources management are necessary for two distinct levels, the higher-level resources management and lower-level delivery management. Although the set of institutiate unit for the analysis and management of water resources, especially when water availability at the basin level becomes the primary constraint to agriculture. The institutional framework for water resources management in a river basin context consists of established rules, norms, practices and organizations that provide a structure to human actions related to water management. Figure 2.1 shows various layers of the institutional inter-linkages in water sector in a river basin context. Accordingly, law and policy are seen together to define the structure for the functioning of water administration. This has been considered as a guideline for analysis and evaluation of the water institutions through the study of delineation an analysis framework capable of capturing the linkages among different water institutional components (inter-linkages).

Following the concept of Saleth and Dinar (1999) on the interlinkages among institutional components in a river basin context as seen in Figure 2.1, Bandagonda (2000) categorized the term “institutional framework” in three interrelated elements: (1) policies, including national policies, local government policies, organizational policies; (2) laws, including formal laws, rules and procedure, informal rules, norms and practices, internal rules of organizations; and (3) administration, including organizations at policy level for resources management and organizations at implementation level for delivery management. Accordingly, the established organizations are to be viewed here as a subset of institutions. Bandagonda further stated that at the macro-level or basin (sub-basin) level, analysis should deal with institutional arrangements that concern inter-sectoral allocation of water such as for irrigation, domestic water supply, hydropower, environmental purposes and other users which depended on common water source. While the service-level analysis should focus institutional issues relating to the mons can collectively cover both levels, often separate organizations are useful to handle the two levels of management tasks (Bandaragoda, 2000). With recognition of the significant reuse of water, the river basin has been considered as the appropriultiple use of water within the irrigation service area.

1.2 Institutional Options for Management of the Irrigation Systems

Irrigation system is the application of technology to extract water from its natural settings to deliver and apply it to soils and/or crop for the purpose of agricultural production and to remove excess water and salts from the soil (Vermillion and Sagardoy, 1999). The irrigation systems are run by different organizations. Organizations are defined as “networks of behavioral roles arranged into hierarchies to elicit desired individual behavior and coordinated actions obeying a certain system of rules and procedures” (Cenea, 1987). While roles are sets of expectations and tasks associated with particular functions (Coward, 1980), they do not necessarily coincide with specific organizations.

There are a number of familiar models for management of irrigation schemes through out the world, such as a line irrigation department, a regulated public utility, or an irrigation district, but these names often mean different things in different locations and varying things to various people. Moreover, there can be a great many variations on each particular model. Johnson III et al. (2002), identifying a number of these varieties of management models, stated that in one location where a so-called utility model prevails, the utility itself may hold a water license and own the physical water control facilities, while in another, the utility may lease the facilities from the government and rely on a water right held by the government. In some locations where the irrigation department model is utilized, some Indian states for example, maintenance may be done primarily by force account. While in others using a similar model, Guyana for example, most maintenance may be contracted out. These familiar labels are thus often ambiguous and fail to communicate clear meanings.

Irrespective of the name that the organization stand by, the authors further proposed that the organizations should be framed into the roles played, the structures of individual organizations, and the various functions that the organizations carry out. Accordingly, the types of organizational arrangements for service provision can be classified based on a set of core attributes that are clear and unambiguous. This can be done by making a fundamental distinction between organizational governance and functional performance. The authors pointed out that the governance functions provide top-level guidance and control as opposed to providing services. In this sense, organizational governance constitutes the higher-level control of the organizations. Governance operates within the confines of public policy to make top-level decisions such as appropriate budgets, setting prices, programming approval, setting terms and conditions for employment of staffs, specifying internal policy and strategic planning. The outputs of the governance process are decisions that shape the functional performance of the organization. Whereas, the functional performances for the irrigation service provider include water allocation and distribution, system repair and maintenance, income generation, conflict resolution, representation in basin, and water resources level distribution and other internal supporting services.

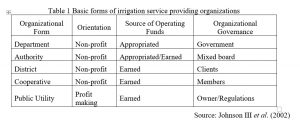

Another important dimension defining the nature of an organization is the source of funding, both operational funds as well as long-term capital financing. In this regard, organizations, which fund themselves entirely through the sale of goods and services, are clearly in a different class from ones which receive their annual budget from the public treasury. And within the group of self-financing organizations are those which intend to make a profit and those which intend to provide goods and services while simply breaking even. These classifications provide a way to make a basic typology of irrigation service providing organizations – profit orientation, source of operating funds, and locus of organizational governance. A classification of five common organizational types of irrigation systems in these terms is summarized in Table 1.

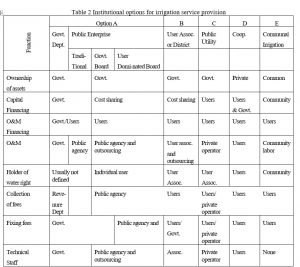

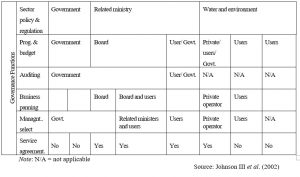

In more specifically, based on particular needs, the authors added a variation to each of three of the governance categories – Departments, Authorities, and Cooperatives – yielding a total of eight. It also includes other system attributes in the matrix, such as ownership, and adds categories for particular management and governance functions. A customized framework for assessing institutional options is given in Table 2.

On the other hand, organizations differ in their capacity to cope with different levels of complexity. This capacity is determined primarily by the organization’s basis of authority, mode of financing, incentives and control mechanisms. Vermillion and Sagardoy (1999) identified six basic non-governmental organizational models which are used for managing irrigation systems around the world. These include integrated water user’s association, public utility, local government, irrigation district, mutual company, and private company. The characteristics of these different types of organizations are summarized in Table 3.

However, in practice, organizations may represent variations and combinations. Although some service providing organizations fit neatly into the typology mentioned above, others do not. There are many variations on these themes, both in the area of finance and

governance, and the variations may be more common than the pure types. An irrigation district, for example, may be a recipient of various public subsidies, as in the United States, but still be considered as self-financing because the variable component of its income is earned. More than one role can be played by a single organization, as when the roles of bulk water provision and irrigation service provision are played by the same agency. A complete role can also require simultaneous action by a number of different organizations – a set of water user associations (WUAs) in an irrigation system, for example. Similarly, a single role may be split among a number of different organizations, as when an irrigation service provider performs some functions itself and contracts out others to third parties.

Seldom today is a single monolithic irrigation organization having total responsibility for and absolute control over irrigation water deliveries from river to farm. Thus several organizations may typically involve in making water deliveries to farmers. With this regard, irrigation service provision involves various stakeholders such as state agencies, farmer organizations, and farmers themselves which must interact and corporate if the irrigation project is to function effectively. Organizations may be combined in several different ways. An example is so-called “jointly managed” irrigation system, where a government agency manages the main and branch canals and farmer associations manage distributary and field channels. The joint management between government and farmer associations is the approach followed in some states in India, Vietnam and Indonesia, where a government agency and farmer organizations are responsible for managing irrigation systems at different levels (Johnson III et al., 2002; Vermillion and Sagardoy, 1999). In such joint management system, important decisions, such as regarding cropping patterns or rotational irrigation, are, in principle, made jointly by government officials and farmer representatives. In medium- to large-scale systems in Sri Lanka, “joint management committees” meet at distributary and main levels to make key management decisions (Vermilion and Sagardoy, 1999). In large irrigation systems in Mexico, the government commonly manages the intake and main canal while WUAs manage distributary and field channels (Bandaragoda, 1999). Representatives from both sides coordinate between main and distributary levels. Another example of joint management is the North China plain, where irrigation districts have agreements to deliver specified amount of water down to turnouts from the main or distributary canals. Water management, maintenance and crop patterns below turnouts are the responsibility of the users or villages (Vermillion and Sagardoy, 1999; Johnson III et al., 2002).

Vermillion and Sagardoy (1999) identified that the irrigation management is organized according to four basic service relationships, including (1) who defines and governs the service, (2) who regulates the service, (3) who provides the service, and (4) who pays for the service. In this sense, the way these service relationships are structured shall determine who is accountable to whom and for what services.

II. Irrigation Management in Vietnam

2.1. Agriculture and Irrigation Management Combined Evolution

Irrigation development in Vietwnam appears to be as old as the history of agricultural development in Vietnam. Irrigation systems in early times were constructed by local provinces, or their officials, as well as by farmers themselves. A feudal system of land ownership prevailed over much of Vietnam until 1945. During this era, the country was rules by the Nguyen dynasty and French colonial forces with fundamental interests in collecting revenue and maintaining law and order. Soon after the defeat of French colonial forces in 1945, the socialist model of economic management was introduced and central planning dominated the entire contry. In agriculture, this was the period of land, capital socialization and farming collectivilization. The collective agricultural production system was implemented at the Agricultural Cooperative (AC) level in 1960. Under this system, households collectively farmed the land and agricultural inputs, such as fertilizer and pesticide were controlled by the ACs. Irrigation management was assigned the strategic mission to facilitate agricultural collectivization. The state put emphasis on mechanized drainage and irrigation, in order to modernize agriculture with the construction of large irrigation and drainage schemes with a full canal network from primary to tertiary canal levels. Management of all such infrastructures was given to state, provincal, and district hydraulic departments which are centrally-financed public agencies. Farmers were absent from the water distribution (Fontenelle, 1999).

This situation worsened at the end of the 1970s when the government tried to secure collectivist economy through further heavy investments combined with a stronger centralization of production mechanism. Village cooperatives were aggregated into commune cooperatives and districts became responsible for all production aspects, including crop calendar establishment, rice variety choice and full water management. Increasing population reluctance toward collectivized economy and production cooperatives, combined with the dysfunction of centralized production mechanism, appeared to reinforce the economic crisis (Kerkvliet, 1999). The crisis due to an excess of state intervention which cut innovation capaities of farmers. More than a technically based crisis, this is a political crisis (Tessier and Fontenelle, 2000).

The economic crisis situation lasted until the beginning of the 1980s when the Vietnamese gorvernment recognized the failure of ‘great socialist agriculture”. Vietnam then initiated a process of de-collectivization of agriculture, moving toward a market economic system. The government introduced a series of agricultural policies and irrigation institutional reforms. A new contract of production with farming households was created from the Khoan 100 (directive 100), aiming to lease paddy land to households for a fixed contribution with exess yields to be kept by the farmers. It gave back to farmers “ the right to decide the use of their labour and the return of their labour” (Tuan, 1995). It boomed agricultural production and mobilized the farmer for the full responsibility in agricultural production. In 1984, the IMCs, which are public companies owned by the state, were established as a new actor based on provincial boundaries to undertake management of public irrigation systems. The IMCs differ from the hydraulic departments in that they are supposed to balance their accounts through the collection of irrigation fee. Simultaneously, the management of relative small schemes and tertiary canals in large irrigation systems were delegated to the ACs.

The lauching of Doimoi (new deal) in 1986, which consists of the abolition of subsidies and liberization of production activities, and the khoan 10 (directive 10) in 1988, which promotes land redistribution to farming households has created new conditions for agricultural production. Agriculture became more diversified and intensive as farmers could then decide on an individual basis their production activities. Farmers increased the number of paddy varieties and developed direct seedling and increased commercial crop production. In the aspect of irrigation management, with khoan 10, farmers became de factor involved in the hydraulic process as new water users (Fontenelle, 2001).

The policy of economic reform went a step further in 1993 with the implementation of the Land Law, which guarantees farmers use of land for 20 years on paddy land and 50 years for perennial crops. These policies promoted moving away from collective action toward individual or household-based decisions and actions in response to market conditions. As a consequence, the cooperative production system collapsed abruptly. The state launched a Law on Cooperative in 1996 to reform old collectivist bodies into new collective efficient service organizations created on voluntary basis by farmers having common needs and interests. The ACs were no longer considered responsible for production, but becoming more as service organizations for the provision of agricultural inputs to individual households. Thereafter, almost all the communes tried to apply the Law on Cooperative as a legal framework for the operation of the irrigation infrastructures.

2.2. Organizational Framework for Irrigation Management

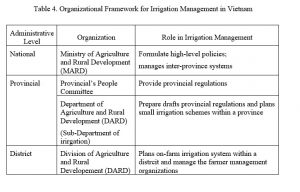

The management of the irrigation schemes in Vietnam is related to various state agencies and local organizations, in which the state agencies are in different administrative levels from the national level down to the commune as presented in Table 4.

At national level

The role of Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MARD) has been delineated in the 1998 Law on Water Resources, that is, it is answerable to the government to carry out the state management function on water resource. MARD operates at the high-level policy and takes responsible in planning, formulating of regulations and procedures for the protection, exploitation and development of major water resource projects. In particular, MARD has the direct supervision of national IMCs which manage the inter-provincial irrigation systems. However, these inter-province irrigation systems are rare in the country. The responsibility for managing existing public irrigation systems and executing smaller projects located within a province is delegated to the Provincial People’s Committees (PPC). Specific policies and procedures on water management may vary considerably among provinces.

At provincial level

The PPC is responsible for organizations and monitoring the implementation of policies and regulations of the irrigation system management. The PPC also provides provisions on policy advices, setting provincial water fees based on national guidelines. Besides, the PPC has the responsibility to co-ordinate with the agencies, organizations and individuals in the reconciliation of the disputes on water resources happened among districts.

The PPC has established a provincial Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (DARD) to implement water-related policies. DARD is a line agency of the province, operating under provincial funding and administration but with technical linkage to MARD. DARD takes responsibility in the planning and design of small projects below 150 hectares. In addition, DARD is in charge of drafting regulations and provincial policies on water resources including irrigation fee calculation, which are finally ratified by the PPC.

In response to the national policy mandating privatization of various government departments, most of the PPCs have established separate irrigation management agencies under DARD to manage all public irrigation systems in the province. In principle, this current institutional framework creates the potential to clearly distinguishing between regulation of the water resources sector conducted by DARD and specific responsibilities of the management agencies. These management agencies are categorized into IMC and water management department. Of which, the IMC is dominated and set up in accordance with the primary hydraulic unit, not by the administrative boundaries. Thus, in some provinces, there are several IMCs that have been formed in a province. IMC is expected to run as autonomous self-financing enterprises in accordance with the degree on public enterprise enacted in 1996. The water management department, on the other hand, is established based on provincial boundaries and functions toward administration, but not as an autonomous self-financing agency.

In contrast, in a few provinces, especially in mountainous provinces, most of the irrigation schemes are small, DARDs are simultaneously in charge in regulation of the water resources sector as well as management responsibilities.

At district level

Various types of irrigation management organizations, which have been established based on the district administrative boundaries, are responsible for O&M of the schemes located within a district. These organizations, such as Irrigation Station (IS), District Division of Agriculture and Rural Development (DDARD), and IMB operate under the authority of the provincial superior related agencies. ISs are subsidiaries of the IMC, in which the IMC directs financial, personnel and other decisions of the individual ISs. DDARD is directed by the provincial DARD while IMB is under the governance of the water management department.

The schemes located in a district may be small schemes or sub-schemes of a large irrigation system. It is usual that the small schemes are managed by the DDARD or by the IMB whereas sub-schemes of a large irrigation system are running by the IS. In these state managed schemes, the joint management structure exists between state agencies and local organizations, that is, state agencies are responsible for management down to the tertiary canal level while on-farm canal system are left to the responsibility of the local organizations.

At commune level

The O&M of relative small irrigation schemes or tertiary canal levels in large irrigation schemes within commune boundaries are conducted by local organizations. In case of large irrigation systems, the local organizations generally serve as intermediaries between the state agencies and the individual farmer. There are several forms of local organizations, such as village, irrigation team, water user association or the agricultural cooperative (AC). The AC is the most common as the last formal level involved in irrigation management.

2.3. Irrigation Management Transfer

The revised ordinance on exploitation and conservation of irrigation works in 2001 promotes decentralization of management irrigation schemes. In this, MARD has issued several policies on promotion of the management transfer of small-scale schemes to local organizations since 1990s. For instance, in Circular Letter No. 1959 (1998), MARD instructed chairmen of People’s People Committees (PPCs) to promote the role of farmers in irrigation management at grassroots’ level by letting farmers setting up management organizations by themselves. So far, the existing policies have just provided a general framework for irrigation management transfer, but specific procedures have not yet been identified. This leads to the fact that, the policies and procedures for management transfer are conducted differently among provinces.

The government has promoted irrigation management transfer for small-scale schemes since the 1990s. Nevertheless, the result of management transfer is modest with an irrigation area managed by farmer organizations of about 0.6 million hectares, which account for 20 percent of irrigated land (DWR, 2003). A major cultivated area of remaining 2.4 million hectares, covering 80 percent is still under the common model of joint management of the state agency and farmer organizations. It is notable that management transfer is mostly applicable to commune-based schemes, although this has been adopted in a lesser degree in inter-commune schemes. Currently, new models for managing inter-commune schemes have been established in a limited number in several provinces.

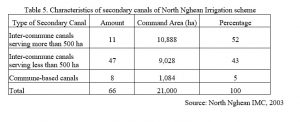

In the state-managed schemes, majority of the secondary canals are inter-commune schemes. So far, there is no investigation to separate the amount of area irrigated by inter-commune canals from the total irrigated area of the state-managed systems. Nevertheless, the majority of inter-commune canals can be evidenced through the situation in the North Nghean irrigation system, which is a large system having a command area of about 30,000 hectares in Nghean province as presented in Table 5.

In the North Nghean irrigation system, almost all secondary canals are inter-commune canals and these canals serve 95 percent of the total irrigated area. Of which, the small canals providing irrigation to command area less than 500 hectares are majority in term of canal amount and provide irrigation for 43 percent of the gross command area. This implicates the efficient institutional reform for management of small schemes is very significant in improving irrigation performance in the country.